Introduction

The Environment has been a prominent part of the political agenda since the 1960s. The expansion of the consumer society after the Second World War in North America and Europe increased the pressure on the environment to such an extent that it became alarming. A more affluent and better educated population showed its concern for the environment and demanded a cleaner and healthier environment. The environmental movement that originated from these concerns was not very historically oriented and regarded the contemporary problems as a unique product of 20th century capitalism and industrial progress. However, some realised that a historical perspective was needed to understand the origins of the contemporary environmental crisis. This is where environmental history came into being.

This essay is divided into two parts. The first and smallest part explores what environmental history is and some or its roots. The second part deals with some of the issues in environmental history and explores the intellectual and philosophical background behind our ecological crisis. This looks in the way people though about the natural world around them during particular different historical periods. But environmental history is not solely an intellectual history and is also about the impact of humankind on the natural world and the influence of the natural world on human history. The final part of this essay will therefore look at the development of agriculture and the impact on the landscape.

This essay is not a comprehensive review of the subject area of environmental history and all the issues it deals with. It is also limited in scope in terms if time span and geographical area, with a focus on Europe and a number of specific periods including the industrial period and the Middle Ages. It is not intended to be an original piece of research, but the text will sometimes reflect the author’s own opinions and criticism and the content also reflects some of the personal interests of the author. These are limited because the discourse of modern environmental history covers such a wide area that it is impossible to review all of this in a short essay. Perhaps this is a sign that environmental history is maturing as an academic discipline.

Environmental history

What is environmental history and what does it mean? Historians studying natural sciences and scientists learning the language of history and the humanities? In 1959 the famous author and scientist, C.P. Snow presented a lecture in which he suggested that the critical intellectual weakness of the later 20th century was the separation of humanities from sciences. These were what he called the “two cultures”, and Snow suggested that in order to solve problems we need to bring sciences and humanities together.1 Donald Worster, one of the leading environmental historians in North America, used Snow’s ideas to show how environmental history in particular needs the talents of historians and scientists working together. In his book The Wealth of NatureWorster also argues that the natural sciences and history have become two separate spheres and therefore historians are not expected to deal with the natural sciences. Historians must deal with people, society and culture and the sciences on the other hand must be concerned with nature. In this way nature is set apart from culture creating two different worlds that are described in different languages.2

The separation of nature from culture obscures the fact that culture is influenced by the nature surrounding it. But it is not a one-way street because culture is also asserting its influence on the natural world. Beinard and Coates included this ambivalent character into their definition of environmental history: “Environmental history deals with the various dialogues over time between people and the rest of nature, focussing on reciprocal impacts”.3 To understand these reciprocal impacts we must try to bridge the gap between culture and nature, between science and history. Environmental history is an attempt to unite the two worlds of science and history. Donald Worster described the essence of environmental history as follows:

Its essential purpose is to put nature back into historical studies, or, to explore the ways in which the biophysical world has influenced the course of human history and the ways in which people have thought about and tried to transform their surroundings.4

Once a historian discovers the connection between nature and culture, a whole field of new subjects opens up and history becomes more interdisciplinary than ever before. It is not only using other humanities and social sciences, but it also starts to use the natural sciences. It is true that environmental history brings many new “characters” on the stage of history. Among these are sciences such as geography, geophysics, biology, demography, botany, and ecology. This is a far from exhaustive list. But working with concepts from other sciences is very demanding for a historian and it demands that he or she is not only trained in history and the social sciences, but also in the natural sciences.5 Commanding all these various specialisms is a formidable task and may require a new type of academic training to produce a generalist.

But not only historians have to broaden their horizons. Scientists must include human history in their work and it seems that they have started to look at historical processes. That is not to say that time has not been a factor in their research because ever since Darwin scientists have recognised that the natural world, even the whole planet, is the product of a long historical process. However, they did not include human culture as an influence in these processes. Although humans are newcomers in the history of our planet, they have had a profound impact on the planet for at least two million years. That means that what we regard as nature is, to some extent, a product of human history. A good example is the use of fire by prehistoric hunters. We know now that the prairies of North America are the product of deliberate burning by Native Americans for thousands of years. This type of management produced a unique ecosystem that European settlers found in the 18th and 19th centuries. For These reasons scientists must take serious the impact of human action, in particularly during the modern period, the past 300 years, when human impact has become deeper and more far reaching than ever before.6

Timescale and spatial divisions

As suggested before, environmental history ventures into all human activities ranging from economics to social organisation, politics, science, philosophy, and religion. Its timescale is not limited to centuries, one thousand, two thousand or even 40 thousand years and it goes all the way back to the origins of humanity and even beyond. It takes into account both the grand planetary processes over long periods of time and the small scale of a locality in a limited time span. Environmental history is global and local at the same time and includes short term and long term processes.

Although environmental history is hardly limited in time and space, most research is focused on the period in which humanity made an increasing impact on the natural world. This period is the most recent geological epoch, the Holocene, which began at the end of the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago and still continues today.7 It is during this short period of time that humanity developed the civilisations agriculture and technologies that had such a profound impact on the environment of our planet. If we go further back in time environmental history becomes less detailed and is covers larger geographic areas and longer time-scales.

Neil Roberts opens his book, The Holocene. An Environmental History, with an outline of the developments after the end of the last glacial period. Here he generalises over large areas and paints the developments of the retreat of the ice sheets in North America and Europe as one grand development. The same applies to the tropics where he describes the shift of climatic zones with not much regard to regional differences.8

As the number of human artefacts produced during the Neolithic period and Bronze Age increases the picture gets more detailed, the scale becomes smaller and the environmental impact more visible. The history of the last two millennia is often so detailed that it is sometimes confusing to see general patterns in the large amount of information available. In this respect research focused on singular localities and short time spans do not provide reliable evidence to reconstruct an environmental history over large geographic areas. Therefore comparative research over large areas combining case studies is important to reconstruct a more reliable picture of general developments and environmental changes.

Some science tools

How do we reconstruct past environments? There is a whole range of tools available to the environmental historian. There are of course the traditional sources of documentary evidence. The problem is that these records are very limited in time and space. For large areas of the world there is no documentary evidence until the modern period. To reconstruct past environments we have to rely on indirect evidence, the so-called proxy records. The term proxy record refers to any evidence that provides an indirect measure of former climates or environments.9

Biological evidence is an important tool for reconstructing past climates and environments. One of the most widely used and successful techniques is that of pollen analysis. It is used to reconstruct the vegetation in the past. An analysis of the pollen grains in each layer can tell us what types of plants were growing when the sediment was deposited and then inferences can then be made about the climate based on the types of plants found in each layer. Pollen can also be used to determine human impact on environments such as deforestation or the extent of agriculture by counting the number of tree or cereal pollen in a sample. Paleoecological reconstruction also uses information provided by the extraction, recording and analysis of the fossil record. This provides us with a time framework and an idea of the flora and fauna during a certain epoch. The problem of fossils for dating and reconstructing past environments is that it is not very useful for the last ten to hundred thousand years.10

Radiometric methods are much applied and are accurate dating techniques. The best known is the so-called radiocarbon dating technique or C14 method. This technique is based on the radioactive decay of carbon 14. The measure of decay is an indication of time that has elapsed since the carbon was formed and trapped in an organism. In addition to radiometric methods dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) and paleomagnetism are used to get a more accurate environmental reconstruction.

Dendrochronology or tree-ring dating is the method of scientific dating based on the analysis of tree ring growth patterns. Since tree growth is influenced by climatic conditions, such as temperature and precipitation, patterns in tree-ring widths, density, and isotopic composition reflect annual variations in climate. In temperate regions where there is a distinct growing season, trees generally produce one ring a year, and thus record the climatic conditions of each year. Trees can grow to be hundreds of years old and so contain annual records of climate conditions.

Palaeomagnetic studies the periodic change of reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field caused that magnetic poles reverse. Paleaomagnetics studies of the rock exhibiting such reversals of the Earth’s magnetic field have assisted in the establishment of a time-scale for the last 4,5 million years.

Past climates can be reconstructed from ice cores taken from the icecaps of Greenland, Antarctica and glaciers all over the globe. By analysing the composition of air bubbles in the ice we can reconstruct the atmospheric conditions and thus the climate during a certain epoch. Cores taken from lakebeds, the ocean floor and peat bogs are also tools to reconstruct past climates. The changing fossil contents of these cores are indicators of ocean water temperatures, environmental change on the land and increasing or decreasing erosion, which is linked to precipitation.11

Landscape reconstruction is the work of geologists and geomorphologists. The geologists provide information on the structure beneath the land, past changes in this structure, sedimentation and the time framework. The geomorphologist looks at the shape of the landscape and combines the information of endogenic processes (processes from within the earth), provided by the geologist, with the erosive power of water, wind and other exogenic influences. One such influence is the human impact on landscapes, soils, drainage systems and vegetation. In this respect we humans are a geological power. The understanding of the influence and development of human impact on the landscape is the domain of archaeology. Archaeologists reconstruct the development of field systems, occupation patterns and technology available in the past.

The techniques to understand environmental changes in the past developed independently within different disciplines, and are commonly practised without much concern to the record of human influence. However Mercer and Tipping observed that “increasingly … the influence of the landscape on people, and of people on the landscape, have come to be regarded as seminal problems in palaeoenvironmental research”. They concluded that the combined range of techniques from the different disciplines have “the potential to move beyond providing a ‘background’ to human settlement, and to explore the complex ‘feedback’ linkages between anthropogenic and natural processes, and to generate a more holistic understanding of … landscape evolution”.12

Origins of environmental history

At the beginning of the twentieth century geographers stressed the influence of the physical environment on the development of human society. The idea of the impact of the physical environment on civilisations was first adapted by historians of the French Annales School to describe the long-term developments that shape human history. Other influences were the emergence of world history and the interdisciplinary method. By the late 1960s the term environmental history was coined by Rodrick Nash and he provided one of the earliest definitions.

Environmental history is probably more developed and institutionalised in North America than in other parts of the world.13 This is due to the American experience of settlement and the consequences for the natural environment. Initially American scholars were concerned with the damage done to nature and the heroic rise of the conservation movement. They studied the institutions and agencies of natural resource policy and protection and were concerned with conservation heroes such as David Thoreau, John Muir and Aldo Leopold.

The rise of this new type of history coincided with the rise of the modern environmental movement and the emergence of public concern over environmental issues as a major public concern in the 1960s. This was fuelled by the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962, the Report for the Club of Rome, Limits to Growth, at the beginning of the 1970’s and the foundation of the Greenpeace movement, among others. It was in this mood of environmental concern that the new discipline of environmental history came into being and historians started to look for the origins of the contemporary problems. We can distinguish several branches in environmental history including green history, the ideas of environment and nature throughout history, pollution and degradation history, to mention only a few. Let’s consider some of these areas in more detail.

The philosophical approach: green history

This type of environmental history is anthropocentric and part of the more traditional approaches of political, administrative and intellectual history.14 It can be described as “green history” and charts the origins of environmentalism and the roots of our modern attitudes towards nature. To understand the origins of modern environmentalism and our attitudes to nature we need to enter into debates about the nature and origins of contributing fields and currents such as the Frankfurt school, Romanticism, oriental philosophy, monism, rationalism and even Nazism. That is what Anna Bramwell does in her book Ecology in the 20th Century. This book, as she explains in the introduction, examines “the thinkers who represent most significantly the roots of ecological ideas”.15 But this kind of history is not limited to the 20th century and its origins can be traced all the way back to antiquity.

It is often said that Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers lived in harmony with nature. In his book The Idea of WildernessOelschlager shows himself an adherent of this idea and for him it is the starting point of the evolution of the human perception of nature and wilderness. During the Palaeolithic time of harmony there was plenty of food and resources for humans and the conception of nature was that humans were part of it an that time and nature was cyclical. During the Neolithic period when agriculture was introduced a split between human culture and nature emerged. Humans increasinglu regarded themselves as separated from nature, and that nature was designed and created for their benefit. If land was not suitable, humans had the ability to alter it and make it useful. According to Oelschlager is this development the moment that natural degeneration began. The result of the emergence of agriculture in the Near East was that Mediterranean peoples became increasingly adept at and aggressive in their endeavours to humanise the landscape. On the other hand the increasing reliance also made them aware that their civilisations depended on nature but also of their distinctiveness of nature. As a result of this contradiction they devised increasingly abstract and complicated explanatory schemes to explain human separation and domination of nature but also failure to control nature, for example in the case of flooding or drought. The limitations of mastery over nature were explained with forces beyond human control such as deities. But in general the Mediterranean landscape was regarded as divine and designed for humans to live in, to alter at will and to dominate.

Out if these rationalisations emerged Greek philosophy and Judaism. Both traditions rationalised the world in their own way. Greek rationalism abandoned mythology for explicit theory and definition and Judaism rationalised the world using a metaphysical framework that explained the world in a metaphoric, allegorical and symbolic way. Judaism and Greek rationalism came together in Christianity within which the philosophical edifice of Platonism was used to create the concept that ruled the west for the past 2000 years.16

Greek rationalism and Christianity created a concept in which nature was conceived as having no value until humanised. Two other aspects of this tradition are anthropocentrism and the linear conception of time instead of cyclical. This meant that history was teleological, which means that it was pointing in one direction to an ultimate goal of perfection. This manner of thinking is known as the Judeo-Christian tradition. In environmentalist literature it is not uncommon to blame the roots of our ecological crisis on the attitudes of the Judeo-Christian tradition towards nature. Lynn White, an American historian, first conceived this hypothesis in 1967 and published his ideas in an article in Science entitled “The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crisis”. In this article he argued that Judeo-Christianity preaches that humans are separate from and superior to the rest of nature. He wrote that “Christianity … not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted that it is God’s will that man exploit nature”. In this view nature was created by God to be used and dominated by humankind. According to White, this attitude has translated into harmful attitudes and actions towards nature with the application of technology during.17

Although White’s thesis has become a forceful argument used by the environmental movement, it has also been heavily criticised. Pepper sums up some of the most important criticisms and notes that other non-Christian cultures have also abused nature. For example, the ancient Romans exploited nature more intensive than medieval Christianity by exhausting soils in North Africa and destroying forests around the Mediterranean.

The same can be said about the idea of the domination over nature granted by the Christian doctrine. Again, it is not unique and other religions are also stressing human domination over nature. A very important aspect of criticism is the fact that during the Middle Ages older magical, astronomical and spiritual traditions were still more important for most people than White presents it and he tends to overlook other and older cultural influences that are present under the Christian surface. Last but not least, Pepper adds that White overestimates how much religious values influenced general values and actions towards nature during the Middle Ages. It appears that material changes are more important and powerful than religious ones. The rise of capitalism made Christians exploit nature on a scale never seen under the Judeo-Christian doctrines. In the end capitalism had a much greater impact on western attitudes towards nature than theology because the rise of capitalism commoditised nature, labour, and land. The cause of this development was the transformation from feudalism to capitalism during which previous pressures to get more out of the land were intensified. Thus the ideology of (scientific) agricultural improvement gained sway.18

It has also been argued that there were theological reasons to drain marches and clear forests. According to Midgley was wilderness a challenge to the medieval mind. It was regarded as a “horrid desert of wild beasts” and as the source of all paganism and evil. Cultivating and taming the wilderness was seen as a contribution to the fulfilment of God’s plan (the linear conception of time). Simultaneously it exercised human dominion over nature and exterminating paganism.19 But we might wonder if people in the Middle Ages actually looked upon nature as described by Midgely.

The period before the Renaissance was monistic rather than dualistic, which means that the cosmos was regarded as a whole in which humans were microcosms in a larger order. The medieval view of nature was that the world was a divine organism in which every plant, creature, every thing had its place given by God. This place was to be found on the “Chain of Being”. This chain hung from the top of the hierarchy, the place were God resided, to the four basic elements, earth, air, water and fire. God was the source of life and did not remain in himself and spilled over, generating in plenty and bringing life to the things lower on the chain. In this way all things were linked and interdependent as an organic whole and if one part of the chain was removed, the whole chain of being was in jeopardy. It was as if an organ was cut out of a humanbeing and without the organ he cannot live.20 Achterhuis adds that the metaphor used for the divine organism was that of the ancient image of Mother Earth. This metaphor was used until the start of the modern period.21

During the Renaissance nature was seen as a book made up of a system of signs and this book needed to be carefully read and studied in order to understand the cosmos and our place in it. The endeavour to “read the book of nature” carried the seed for the Scientific Revolution. The search for the cosmic order led to the discovery of the heliocentric cosmos, Kepler’s laws of the planets’ orbits and ultimately Newton’s laws describing gravity.22 In the 17th century scientists and philosophers tried to understand God’s creation with the new scientific paradigm that was emerging. They saw the scientific method as an instrument to read the book of nature. Anyone who could read the book and understand nature was able to understand the will of God. He was regarded as the “watch-maker”; the supreme designer and engineer of nature which was made in His image and according to His plan. However, it became soon clear that the founders of modern scientific thought, among them Bacon and Descartes, abandoned the theological foundations of science. For Bacon the aim of science was “to lay the foundation, not of any sect or doctrine, but of human utility and power” in order to “conquer nature in action”.23 To achieve this goal the scientific method was seen as the foundation of all human knowledge. The scientific method is analytical, experimental and reductionist and seeks to understand the world by taking the “machine of nature” to pieces to see how it works. Mathematics became the language to describe real knowledge about the world. In doing so the new paradigm became: what truly real is, is mathematical and measurable; what cannot be measured cannot have true existence.24 According to Descartes nature is governed by “natural laws”, which can be measured but as a result nature disappears behind a facade of measurable and abstract quantities. What we normally call nature is completely disappeared with Descartes and reduced to numbers; hence this is called the reductionist method. For Descartes nature was a realm that cannot be observed by our own sense but can only be known through the power of reason, what means by rational thinking. In this way nature is reduced to a tool that can be used for the benefit of human society.25

According to Descartes and his contemporaries was science progressive in two ways:

- It was build upon the secure basis of facts, advancing from them towards greater and greater truth.

- Science was equal to human progress; it was an instrument to improve humanity’s material circumstances.

During the enlightenment the idea of human progress was extended. Science was to be not just the means of improving society’s material circumstances, but also the means of commanding human nature to improve social and moral conditions.26

It is fashionable within environmentalist and conservationist cycles to regard Descartes and Bacon as villains who are guilty of degrading nature from a living organism into a dead mechanism that can be manipulated at will. But this judgement is possibly too simple. In his introduction to Bacon’s New Atlantis Weinberger notes that Bacon “knew that the scientific transformation of the world would have extraordinary moral and political consequences and that it would pose new problems in place of old ones”.27 Bacon’s writings about modern science seem more critical in this light than at first sight. He is not just proposing a mere revolution in human reasoning and mastery of nature but is also aware of the changes in human relations during and after the conquest of nature guided by science. Bacon questions if the outcome of this project is always positive one.

The period during which European society regarded nature as something that could be used at will and changed limitlessly to meet our needs did not last for long. Already during the 17th century the destruction of nature in Europe intensified to such an extent that it was probably more visible for the people than our contemporary environmental problems are for us. A much-cited text to illustrate the extent of environmental problems in the 17th century is John Evelyn’s description of the air pollution in London. He wrote:

This pestilent smoak, which corrodes the very yron, and spoils all the movables, leaving a soot upon all things that it lights: & so fatally seizing the lungs of the inhabitants, that the cough and the consumption spare no man.28

One might argue that this was only a local environmental problem that cannot be compared with our continental-wide and even global problems such as global warming. But in Evelyn’s time the consequences of centuries of forest clearance and transformation of the landscape into cultivated agricultural land were painfully visible. Evelyn published in 1664 Silva: or a Discourse of Forest Trees in which he pointed at the destruction of the last forests in England. He was among the first to plead for conservation and a sustainable management of the forests. This classic of the so-called Conservation Movement is followed by many publications repeating the same message: there are limits to human exploitation of nature. To avoid an environmental crisis humanity must behave more responsibly and act as a steward managing and protecting nature.

This is also the message of the so-called Brundtland Report that was published by the United Nations in 1987. This report stated that we have to behave as good stewards of the earth, creating sustainable development. The Brundtland Report defines this last aspect as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.29

But would the call for more responsible behaviour and sustainable use of nature work this time? If we look at the history of the relationship between humans and nature, one can only be very sceptical. In spite of all several warnings of the past three centuries human impact on nature has intensified manifold since the 17th century. It seems that modern proposals for solving environmental problems are merely old ideas in new guise. We are reinventing the wheel and present sustainable development and good stewardship as new solutions to recent problems. It appears that our current problems and the rise of modern environmental concern in the last forty years or so are working as a lens that obscures the past. The 19th century debate about climatic change caused by the clearing of the Indian forest and the debate about the effects of overpopulation (Malthus) shows that concern for the environment is a continuous story. Studying environmental history shows us that our current problems are not so new and unique as many of us think and that they are the products of a long historical process.

The colonial context

At the same time of the scientific revolution the European powers were in the process of rapid colonial expansion. To make the new discovered lands economic useful, the study of plants, animals and geography was stimulated and it is with this context that we must put the appointment of botanists and other scientists in service of the East Indian Company and other colonial authorities and the activities of missionaries and surgeons as naturalists.

The publication of Linnaeus’ The Oeconomy of Nature in 1749 laid the foundation of modern botany and biology. He saw a perfect hierarchy in the natural world and thus he categorises all plants in a system of families and genera. This reflects the belief in the “divine order of nature” which is related to the medieval idea of the chin of being and which had not yet entirely disappeared. Curiosity about the environment and natural world was thus rising and in this atmosphere Alexander von Humboldt voyaged the world to discover how the balance of nature was achieved. Humboldt was a German scholar and explorer whose interests encompassed virtually all of the natural and physical sciences. He laid the foundations for modern physical geography, geophysics, and biogeography and helped to popularise science. However, another voyage, that of the Beagle, led to the development of the theory of evolution by Charles Darwin. The idea of evolution proved vital to the creation of ecology as a science. Darwin recognised, according to Derek Wall, other species as “our fellow brethren” and he was critical about animal abuse, deforestation and hunting.30 The publication of The Origin of Species coincided with that of the work by Ernst Haeckel who coined the word ecology in 1866. He defined ecology as the study of the web of relationships that link all species, including humanity.31 This definition of ecology provided the later green movement with a scientific underpinning of their belief in “holism”.

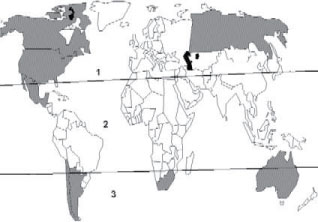

The link between the development of ecology and the colonial context provided the background for a distinct type of environmental history: the impact of imperialism and colonialism on the natural world. Where the Americans had taken Thoreau, Leopold and Muir as the beginning of modern environmentalism and conservation, Richard Grove is pushing the origins back into the 18th century. He argues that the European expansion produced a situation in which tropical islands were seen as symbolic locations for idealised landscapes, images of the Garden of Eden. The commercial exploitation of tropical islands and India led to environmental degradation of these islands and local extinction of plant and animal species.32 The first botanists, mostly physicians and surgeons of the Indian Companies, were alarmed by these developments. This led to an increased anxiety about human caused regional climatic change and species extinctions during the 18th and 19th centuries. In the wake of this concern the first measures were taken by colonial authorities to prevent deforestation and protect rare species. This concern for the environment reached a climax around 1860, when the Indian Forest Service was established, almost 60 years before such as service emerged in Britain. Grove typified these years as the “environmental decade”.33 Colonial history added the global perspective to environmental history and explores the destructive powers unleashed on a global scale by European colonialism and exploitation as well as interaction with local environmental management regimes. Alfred Crosby explored in this context the role of bio-ecological factors in the Europeanisation of large parts of the world, in particular South America. He argued that there are two distinctive ecological realms. The first contains the temperate zones of the earth comprising North America, the southern part of South America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. The second area covers roughly the tropical belt of the world (map 1).

The biological differences between both zones defined the success of European settlement. Between 1820 and 1930 about 50 million people emigrated from Europe and most of them settled in the temperate zones where they have been extremely successful. In the tropical zone, European settlement practically failed and the causes for this phenomenon are of an ecological kind. The ecological system of the Old World was extremely aggressive in comparison to the ecological system of the Americas and the other white settlement colonies. The invasion of European diseases, such as measles and smallpox, and the introduction of animals and plants caused a disaster among the indigenous populations and ecosystems. The fate of the Central and South Americans empires is well known. Their where practically decimated by disease after the arrival of the Spanish at the start of the 16th century. The Spanish conquerors brought smallpox and venereal diseases and over 90% of the population died in the decades that followed. Before the European conquest the Mexican population is estimate to have numbered between 25 to 30 million. By 1568, less than 50 years after the first contact with Europeans, the population had shrunk to about three million.34

In their new environments, European crops and cattle flourished better than in the Old World and they adapted quickly and overwhelmed many local species. In this way they provided a sustainable environment for the European settlers and without the success of the European ecological system in the colonies, it is unlikely that the settlers would have succeeded in occupying North America, Argentina, New Zealand and Australia in only a few generations. Crosby assigns what he calls the “biotic portmanteau” of plants, animals and diseases a leading role in the process of demographic take-over.35 Crosby has dubbed this exchange of disease, plants and animals between Europe and the America’s the Columbian exchange.36

But Crosby was not the first to recognise biological factors as a driving force in history. William McNeill discussed in his book Plagues and Peoples the importance of epidemics and disease in world history. He concluded that “Infectious disease which antedated the emergence of humankind will last as long as humanity itself, and will surely remain, … , one of the fundamental parameters and determinants in human history”.37 McNeill’s and Crosby’s work on ecological imperialism and epidemics brought the microbiological world in the realm of historical explanation.

Degradation of the natural world

Another important leitmotif in environmental history is the degradation of the natural world caused by human activities. A good example of this theme can be found in the introductory chapter of Clive Ponting’s A Green History of the World in which he describes the decline of the civilisation on Easter Island, which was in part caused by environmental degradation. Ponting’s green history is one of degradation and devastation of the natural world caused by humans. Ponting points out that:

Over the last 10.000 years human activities have brought about major changes in the ecosystem of the world. The universal expansion of settlement and the creation of fields and pastures for agriculture, the continual clearing of forests and other wild areas, … , have steadily reduced the habitats of almost every kind of animal and plant.

Ponting concluded:

Past human actions have left contemporary societies with an almost insuperably difficult set of problems.38

This is a rather gloomy vision of history, however, one cannot hide from the fact that past human action has affected the planet on a global scale, changing the natural world. But to present most changes as decay caused by humans is probably a rather narrow-minded approach because the natural world itself is never static but always evolving. It is changing so rapidly and leaves such a deep imprint on human society that we might search in vain for a recognisable stable state of nature. It is in this context that Beinart and Coates write that “the very notion of a self-regulating, stable ecosystem may be more metaphysical than actual”.39 They add that concepts of the natural world are always cultural statements. Worster also observed this and wrote about the work of scientists and other scholars “that their ideas of nature, … are the products of the cultures in which they live”.40According to David Pepper one of the tasks of green or environmental history to is study these ideas and perceptions about nature. He argues those different representations of “wilderness” and “nature” have political and ideological dimensions. The task of environmental historians is to dissect these representations, reconstruct them, trace their origins and place them in their historical context. In doing so historians can show how little these ideological perceptions have to do with the real natural world. In the words of Stephen Budiansky, most perceptions of nature are “good poetry but bad science”.41

One of such perceptions is that nature is capable to quickly recover from human interference, especially if aided with good management policies. Pepper calls this the “myth of nature benign”. Many proponents of the free market economy favour this perception because it does not require any action or interference from humans, or narrowly defined the free market. On the other side of the perception spectrum we find the idea that nature is very vulnerable and easily damaged by human activity. Therefore humans must be cautious about any development and even regarded as acting outside of unspoiled nature. This perception is coined the “myth of nature ephemeral” and is popular among deep of radical environmentalists. A third perception is that of the idea of “nature perverse/tolerant, that holds that development is acceptable as long as the limits and laws of nature are observed”.42

The cultural filter

According to Pepper each perception or myth functions as a cultural filter that determines how adherents of different perceptions perceive the environment at the present day and in the past. Oelschlager uses the concept of the cultural filter in his book The Idea of Wilderness and his thesis is that the perception of wilderness depends on the historical and cultural filter humans used in different periods. He argues that the modern historical lens obscures the idea of wilderness in ancient times: “Through the lens of history human experience takes place outside nature”.43 Oelschlager tries to drop the modern lens, and he argues that historians must always be aware that images of the world around us are not the same as the real world. They are mental categories, concepts that try to describe the real world. These past concepts might differ from ours but we must careful in judging it because is always easy to be wise after the event.

By studying the social and historical filters, historians can reconstruct a perceived environment and explain particular opinions and actions of distinctive groups. This will help us understand how others and ourselves arrived at the present set of attitudes and ideas and to evaluate them critically. This will also help us to identify misconceptions in environmental thinking and perceptions about nature. It will contribute to stimulate the development of new environmentally sound concepts and attitudes. Here we touch directly upon the political and ideological aspect of environmental history and we must be aware that there is a long tradition in western thought about the “noble savage” living in harmony with nature. Much contemporary environmentalist literature portrays pre-industrial and pre-colonial communities as “children of nature” or “paradise people” who did not loose their innocence. These people are portrayed as having lived in harmony with the land and not disturbing its natural balance through the application of technology or demographic pressure. This idea is also an important force in political arguments used by native people especially in North America, Australia and New Zealand. Unfortunately for these people recent historical, archaeological and anthropological research showed has that their ancestors were capable to manipulate and modify the natural world to their advantage through the use of fire and hunting. Pre-historic settlers of the America’s, Australasia and Europe might have been partly responsible for upsetting the ecological systems and the extinction of many grazing animals through over hunting and persistent burning of large areas. According to Beinart and Coates these early migrants were aggressive colonisers in their own right. They concluded that the revival of “aboriginal ideas” of nature by descendants of native people “is a powerful ideological statement rather than good history”.44

Humans and the physical world

The preceding pages have dealt with the intellectual and philosophical side of environmental history. But what is the place of humans in the natural world? Human history is not only the story of the impact of its actions on the physical environment. It is also the story of human reaction to the changing natural world. It is the story of climatic change, slow geological processes, species extinctions and biological changes. The history of the relation between humans and their natural surroundings is a tale of interaction and no one way street. The following paragraphs will focus on the importance of the natural environment in the development of human history from prehistoric times up to the Middle Ages.

Where do Humans fit into nature? It is possible to apply all kinds of definitions to our species, such as intelligent, tool-using, social, able to think abstractly, conscious of the environment and of time. Organised in massive groups and armed with technology we manipulate the environment, transforming the face of the earth to satisfy our needs. It is only during the last 2.5 million years that the genus Homo has formed part of the biosphere. Up to about 10,000 years ago the various human species lived the same kind of life: that of nomadic hunter-gatherers. Then at the end of the last Ice Age, around 10,000 ago some people in the Middle East and slightly later in other places began to cultivate some edible plants and domesticate animals. In a process that took centuries or even millennia, agriculture and stockbreeding became the major forms of subsistence. This development occurred first in the so-called Fertile Crescent in the Middle East but during the following millennia agriculture developed independently in the Yellow River Valley, the Indus Valley, in New Guinea, in the region south of the Sahara and in Mexico and Peru. These regions are called the core regions of agriculture.45

It is very likely that humans manipulated nature much earlier than the first development of agriculture. An intriguing question is why prehistoric hunter-gatherers did abandon their way of life in favour of agriculture? The classical explanation is that in the core regions the climate changed and humans and animals were forced to retreat into refuges around rivers and in oases. They had to look for more efficient ways to produce food. The solution was agriculture. This so-called ‘oasis hypothesis’ was first introduced by Childe in 1923. But research in recent decades has made clear that the pattern is more complicated. Pollen records and lake sediments point to a wetter climate at the start of the Holocene, not a drier. The same applies to Mexico. The result of this was that plants, the ancestors of our major agricultural crops, spread over larger areas. In this way the plants became more abundantly available than before.46

In the Sahel/South Sahara conditions got drier so that cultivation of crops was not an option. The savannah landscape that developed attracted large herds of animals. Some species were domesticated and stockbreeding became the dominant means of subsistence. Childe’s hypothesis was related to the whole area of the Middle East. But it is very likely that the most important recourses were found in the area immediately adjacent to where people lived. This led to diversity in the development of agriculture. Agriculture probably did not originate in a few core regions but over large areas. The problem is that the evidence is very sparse and scattered over enormous areas.47

The rise of agriculture and domestication led people to give up their nomadic life and settle down. In this way the first villages came into being and became the forerunners of the first urban concentrations. The oldest known walled city in the world, Jericho in Israel, dates from 9800 BP. The development of urban centres sparked off a cultural revolution that transformed humankind radically. Social hierarchies, specialisation, art and science emerged. Societies evolved from tribal bands via chiefdoms into states. This cultural revolution speeded up with the development of metallurgy and writing. It caused also environmental degradation.

The most damaging activity was undoubtedly agriculture. It transformed complete landscapes. According to Roberts the link between people and nature weakened with the advent of complex agricultural societies. Nature became less the “habitat” for the farmer and more a set of economic resources to be managed and manipulated.48 However, the impact of early agriculture was limited, although here we can not generalise. In Europe the majority of wildwood remained untouched for a long time. The fate of the early agriculturists was interwoven with the habitats they occupied. In the Middle East the local impact was much greater due to sedentary settlement and permanent farming. In Europe farming took for a long time the form of shifting cultivation.49 But over the course of time farmers settled permanently and during the Bronze Age the impact of farming was considerable through the introduction of the scratch plough and animal traction. According to Roberts this epoch was the ‘high tide’ of upland farming in the British Isles. A combination of climatic change and human misuse of fragile environments afterwards caused the decline.

It was believed for a long time that when the Romans came to the British Isles they encountered a dense, inhospitable and undisturbed forest wilderness. A penetrating description of this perception can be found in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. He describes the arrival of a Roman army officer in the British Isles and what impression it might have been made on him.

Here and there a military camp lost in the wilderness, like a needle in a bundle of hay – cold, fog, tempest, disease, exile, and death – death skulking in the air, in the water, in the bush.

And further:

Land in a swamp, march through the woods, and in some inland post feel the savagery, the utter savagery, had closed round him, – all that mysterious life of the wilderness that stirs in the forest.50

However, it is very unlikely that anyone sailing to the British Isles two thousand years ago would have found a dense, forested wilderness. The later Bronze Age and pre-Roman Iron Age (3000-2000 BC) was probably the most active period of forest destruction in British history. Thus the Romans encountered not a thick-forested Island but took over a landscape that was already largely agricultural.51 According to Rackham the Romans found a landscape that was already parcelled into ownership. What the Romans found was a pattern of enclosed fields. In the literature these field are often labelled Celtic Fields. This is the traditional name for small, enclosed fields in all kinds of regular shapes that covered thousands of miles on chalk down land, moorland, and other terrain.52 It is very likely that the size of the fields differed and that older field systems of the Bronze Age were still in use. Climatic changes and the local geography also defined local differences in cultivation. In Dartmoor agricultural land on marginal upland sites was abandoned during periods of climatic deterioration. In the colder period between 500 BC – 400 AD villages were displaced to the valley bottoms. Climatic deterioration in the 14th century affected elevated fields from Dartmoor to the Scottish Highlands. Many elevated fields were abandoned. Elevated marginal grounds are extremely vulnerable to the slightest change in temperature and humidity. But human misuse of the land also contributed to changes in the landscape. Germanic settlers caused soil erosion on chalk, gravels and sand by overexploitation in the 5th to 7th centuries. They were forced to abandon these lands and use the heavier clay grounds.53

After the Roman period the enclosed fields were replaced by the so-called open-field system. The origins of this type of field system remain obscure. The open-field arable was made up of long strips aggregated in furlongs and these into fields. Each farmer worked one or more strips in one or more fields. The woodlands and swamp area near a river or stream were normally used for grazing. I will not discuss the way that communities had organised the use of the land and practices used. Figure 1 shows a typical example of an open-field system. The open fields disappeared in the 18th and 19th centuries because of the introduction of a series of enclosure acts.54

One of the central features in the history of the later Middle Ages is the expansion of population and economic activity between about 1000 and 1300. Marc Bloch labelled this period ‘the great age of clearing’ in France. According to Smith this also applied to Britain and Germany.55 However, Roberts concluded “that the distribution of wooded and non-wooded land … recorded in Domesday England had already then been in existence for at least a thousand years”.56 According to him, the changes in woodland cover that occurred in medieval times lay almost entirely in the hands of the dominant social class (nobility, clergy and monarch). In contrast to earlier periods there was no longer common access to woodland resources. The regulation of access to woodlands, conservation and management made economic sense. The reason for this is that during the later Middle Ages the value of timber rose steadily. This provided the landowners with additional income. Therefore forests were protected against damage, theft and misuse.57

Around 1340 the pressure on the land had become critical due to population growth. The Black Death did not end the pressure on agricultural land. This is probably caused by the fact that grain prices remained high until at the end of the 1370s when grain prices declined 30 to 40 percent. It seems that there is a connection between population decline in the 14th and 15th centuries and changes in land-use and agricultural practice. It is suggested that more land came in fewer hands and that there was a shift to more extensive use of the land for grazing. On the other hand increased production of luxury products such as hop and grain for beer production asked for more intensive use of fertile land. However, we must be careful with making generalisations. Bruce Campbell warns that there is not enough evidence for broad generalisations because the data available is too regional.58 Delano and Perry concluded the same: medieval society was complex. There are, therefore, many circumstances that could have affected the ecology of a settlement, and considerable care must be exercised when attributing to climatic variations.59 This is not only true for the Middle Ages but for any period in history. The interaction between the environment and culture is always a highly complicated one.

Applied science

Now we have to consider briefly how environmental history works and what its key characteristics are. Environmental history is not so much a subject but a market place in which various subjects come together. For example, it is deeply attached to economic history, social history and cultural history; it is closely attached to conservation biology science, environmental science and the earth sciences but also archaeology, which studies the material past and many other subjects. It is almost like a stage where all these actors come on and make their contribution to the field.

Perhaps we can divide the subjects involved in two broad categories: on the one hand there is the study of the material past involving natural processes that shape the world and on which we depend. It also includes the production cycles of agriculture, resource extraction and the use of what we now call ecosystem services. On the other hand there is the study of the cultural past and realm of ideas. How did people in the past perceive the landscapes and environments they were living in? How did they construct narratives to explain the natural world or to justify its exploitation?60

How does an historian approach an environmental history subject in practice? Take for example forest history in the United Kingdom. How to study the forest history of a particular landed estate? There are many documents stored in archives relating to estate management throughout the United Kingdom that go at least several hundred years back in time. Here we can use a straightforward historical approach: go to the archives and see what documents emerge from landed archives. In addition there is also an immense volume of contemporary printed literature related to forestry. In general early scientific literature provides a wonderful story of discovery and the way these people related to the landscape and environment. Examples of this literature are the publications of the Royal Scottish Arboriculture Society, or the proceedings of the learned societies, to mention only a few. There is also a body of instruction books on forestry starting with John Evelyn’s Silva in the 17th century providing insights into the scientific ideas about forestry at the time. All these printed primary sources must be taken into account.

The next step is to see if we can find any cartographic or aerial photographs as well as old paintings, engravings or landscape photographs that show how the appearance of the landscape has changed over time. In addition it is a good idea to consult archaeological surveys to get an indication how long the landscape has been altered and in what ways.

The literary, archival and cartographic research form the bases for your field work in the locality of your study. It is a good idea to bring a camera and photograph elements and things of interest that you have identified in the archival material and on the maps and images so that you can compare this. But this fieldwork can also reveal features in the landscape, such as wood banks, the remains of wears or ancient woodlands that were not mentioned in the archival material or shown on maps. It throws up new questions, for example how long have these woodlands been there? Without documentary evidence this is where science can help out.

For example palynologists, scientists who study fossil pollen, can discover from the pollen cores taken from peat bogs or lake sediments, what the wood, or any vegetated environment, has been like in the past. So, suddenly a historian discovers that science can take him back centuries before there were any documents. Or by comparing data that historians have found in historical documents with his findings a scientist can suddenly learn that a change in land use or the land management regime can explain sudden changes in vegetation that cannot be explained by natural processes. For these reasons collaboration with scientists is one of the most exiting and potentially profitable elements of environmental history.

In more recent times forestry management has become a science and historians should learn some of this when dealing with the 19th and 20th centuries. But there are always areas that are too specialist and which need addition explanation. To get this additional explanation it is an obvious step to approach a forester or a forest expert in a forestry or environmental studies department. In addition as a historian you do not often know exactly where to look for relevant sources and here scientists can also help out.

To summarise the working method of the environmental historian: behave like a historian but learn a little science. This will help to formulate questions that you are not able to answer as a historian and take these to scientists to help you out.

Environmental history has very practical uses and can be applied to help formulate conservation policies, resource management and to understand climate change. For this reason environmental history is a very public type of history that can contribute to contemporary environmental issues. The bottom line is that Environmental history is more of an applied science or an applied humanities subject, depending from which angle you approach it.

Conclusion

In this essay we explored some of the themes, results and issues in environmental history. It is far from comprehensive survey but several themes are emerging from the previous pages. A considerable part of environmental history is dealing with our perceptions of nature and the environment, which is an intellectual history of the relationship between humans and nature. To write this kind of history, historians are using literature studies and, even more important, philosophy to reconstruct peoples justifications for transforming nature in the past. The latter part of this essay dealt with the interaction between humans and the physical world. Here historians are using studies from the natural sciences to reconstruct past environments and the modifications of it caused by human activity.

One of the striking aspects in all of this is the relative truth of environmental history because there are, as should be, no ultimate benchmarks to judge what is good or bad. A “truth” is the product of an interpretation derived from our perceptions of the natural world and the value systems in which these are formed. Val;ue systems change over time and therefore historians studying the past must step back from contemprorary values and reconstruct those of past societies. It is for this reason that there cannot be an ultimate environmental history. This is probably why the intellectual and philosophical explanation of our relationship with nature takes such a prominent place in environmental history. It explains the way in which people make sense of natural world and by doing so formulate justifications for their exploitation of nature, at present and in the past. It is looking for the values applied to the environment by other societies at different locations in time and space. We must therefore realise that research such as excavations, climate reconstruction and pollution histories are not value free. ‘Good’ and ‘bad’ are therefore difficult labels to use in environmental history. In many cases the modification of the environment was a logic and necessary step for the people involved, because for them it had practical, political or economic advantages. It is always easy to be wise after the event and condemn people for what they did or did not. Therefore environmental historians should realise more than anybody else that the world is not divided in black and white. There are only shades of grey and it is the task of the environmental historian to explain these shades and make sense of them.

But doing this is a formidable task because there are so many lines of investigation possible, it may seem that environmental history has no coherence and is rather eclectic. It includes virtually all that has been in the past and that is affecting us. Environmental history could be the crossroad between the humanities and the natural sciences. It links scientific reasoning with philosophical criticism; the physical world with the world of ideas. Environmental history is probably close to what the French Annales-school called “total history” and they argued that history is everything, and everything is history.61 However, by attempting to do this many historians experience a feeling of unease or even fear and become engulfed by the buzzing confusion of past voices, forces, events and relationships but also a dynamic changing natural environment, almost defying any coherent understanding. The totality of environmental history may leave us with a seemingly unmanageable burden of trying to write a “history of everything”, but it is also a challenge and a promise. We did not create nature or the past. Both simply exist and are an integral part of our world and it is the task of historians, scientists, philosophers and others to come together and make sense of it all.

References

2 Worster, D., “The Two Cultures: Environmental History and the Environmental Sciences”, Environment and History, 2 (1996) 3-14; Worster, Donald, The wealth of nature: environmental history and the ecological imagination (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

3 Beinard, William & Coates, Peter, Environment and History: the Taming of Nature in the USA and South Africa (London, 1995), p. 1.

4 Worster, D., “Path Across the Levee”, In: The Wealth of Nature. Environmental History and the Ecological Imagination (Oxford, 1993), p. 20.

5 Beinard & Coates, Environment and History, pp. 2-3

6 Worster, D., “Path Across the Levee”, pp. 24-25.

7 The amount of sediment, rock and soil shifted because of human activity now rivals erosion caused by natural processes. For this reason Nobel Laureate Paul Crutzen has proposed to call the modern age the “Anthropocene”. See: Crutzen, Paul J., ‘Geology of mankind’, Nature, Vol. 415, No. 23 (3 January 2002), 23.

8 Roberts, Neil, The Holocene. An Environmental History (Oxford, 1989), Chapter 1.

9 Lowe, J.J. & Walker, M.J.C., Reconstructing Quarternary Environments (London, 1997), p. 17.

10 Ibid., p. 6.

11 Lowe, J.J. & Walker, M.J.C., Reconstructing Quarternary Environments, p. 7.

12 Mercer, Roger & Tipping,Richard, “The Prehistory of Soil Erosion in the Northern and Eastern Cheviot Hills, Anglo-Scottish Borders”, In: Foster, S. & Smout, T.C., The History of Soils and Field Systems (Aberdeen, 1994), p. 1.

13 Other parts of the world are catching up quickly with increasing output of research in Europe, Asia, South America and Australia. This is reflected in the creation of the European Society for Environmental History, the South Asian Society for Environmental History and the Latin American Society for Environmental history. See links to their websites on the Links page.

14 Beinard & Coates, Environment and History, pp. 1-2.

15 Bramwell, Anna, Ecology in the 20th Century. A History (London & New Haven, 1989), p. xi.

16 Oelschlager, Max, The Idea of Wilderness from Prehistory to the Age of Ecology (London & New Haven, 1991), p. 33.

17 White, Lynn, ‘The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis’, Science, 10 March 1967, vol 155, no. 3767, pp. 1203-1207.

18 Pepper, David, Modern Environmentalism. An Introduction (London, 1996), pp 154-159.

19 Midgley, Mary, Science as Salvation. A Modern Myth and its Meaning (London, 1992), p. 72

20 Pepper, Modern Environmentalism, pp. 131-133.

21 Achterhuis, Hans, “Van Moeder Aarde tot Ruimteschip: Humanisme en Milieucrisis”, In: Natuur Tussen mythe en Techniek (Baarn, 1995), p. 44.

22 Pepper, Modern Environmentalism, pp 125-126.

23 Bacon, Francis, New Atlantis and The Great Instauration (Wheeling, 1989), pp. 16, 21.

24 Pepper, Modern Environmentalism, p. 125.

25 Achterhuis, Mythe en Techniek, pp. 42-43.

26 Pepper, Modern Environmentalism, pp. 145, 147.

27 Bacon, Francis, New Atlantis, p. ix.

28 Evelyn, John, London Revived (Oxford, 1938), p. 6-7.

29 Quoted in: Pepper, Modern Environmentalism, p. 74

30 Wall, Derek, Green History. A Reader in Environmental Literature, Philosophy and Politics (London, 1994), p. 6.

31 Bramwell, Anna, Ecology in the 20th Century, pp. 40-41.

32 Grove, Richard H., “The Origins of Environmentalism”, Nature, vol. 345, 3 May 1990, pp. 11-14.

33 Grove, Richard H., “The Evolution of the Colonial Discourse on Deforestation and Climate Change, 1500- 1940”, in: Ecology, Climate and Empire. Colonialism and Global Environmental History, 1400-1940 (Cambridge 1997), p. 20.

34 McNeill, William H., Plagues and Peoples (London, 1976), p. 189; Crosby, Alfred W., “Ecological Imperialism: The Overseas Migration of Western Europeans as a Biological Phenomenon”, in: Worster, Donald, The Ends of the Earth. Perspectives on Modern Environmental History (Cambridge, 1988), pp. 103-116.

35 Crosby, Alfred W., Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 103-116.

36 Crosby, Ecological Imperialism

37 McNeill, Plagues and Peoples, p. 268.

38 Ponting, Clive, A Green History of the World (London, 1991), pp. 61, 407.

39 Beinard & Coates, Environment and History, p. 3

40 Worster, “Across the Levee”, p. 25.

41 Budiansky, Stephan, Natures Keepers. The New Science of Nature Management (New York, 1995), p. 4.

42 David Pepper, Modern Environmentalism, p. 3.

43 Oelschlager, The Idea of Wilderness, p. 7.

44 Beinart & Coates, Environment and History, pp. 4-5

45 Priem, Harry N.A., Earth and Life. Life into Relation to its Planetary Environment (Dordrecht, 1993), pp. 51-55; Diamond, Jared, Guns, Germs and Steel, pp. 83-191

46 Roberts, The Holocene, p. 110

47 Ibid., pp. 110-111

48 Ibid., p. 128.

49 Ibid., pp. 119-12

50 Conrad, Joseph, Heart of Darkness, p. 19.

51 Roberts, The Holocene, p. 150

52 Rackham, Oliver, The History of the Contryside, pp. 158-160.

53 Delano, Catherine & Parry, Martin, Consequences of Climatic Change (Nottingham, 1981), 31, 35.

54 Rackham, History of the Countryside, 164-166; Fussel, G.E., Farming Technique from Prehistory to Modern Times (Oxford, ), p. 50.

55 Smith, C.T., An Historical Geography of Western Europe before 1800 (London, 1978), p. 163.

56 Roberts, The Holocene, p. 150.

57 Ibid., p. 151.

58 Campbell, Bruce M.S., “A Fair Field once Full of Folk: Agrarian Change in an Era of Population Decline, 1348-1500”, Agricultural History Review, 41 (1993), pp. 60-70.

59 Delano & Perry, Consequences of Climatic Change, p. 37.

60 Worster, Donald, The ends of the earth. Perspectives on Modern Environmental History (Cambridge: CUP, 1988), pp. 289-308; See also: Sverker Sorlin and Paul Warde, “The problem of the problem of environmental history: a rereading of the field”, Environmental History, 12 (2007) 1, p. 112.

61 Harsgard, Michael, “Total History: The Annales School”, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1-13 (1978), pp. 1-13.

Recent Comments