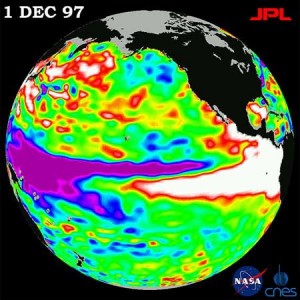

Warm water (white) of El Niño off the

coast of South America in 1997

(Photo: NASA, Source: Wikimedia Commons).

Every two to five years the Pacific experiences a phenomenon that is known as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The name El Niño, Spanish for “the child,” refers to the infant Jesus Christ and is applied because an El Niño event usually begins during the Christmas season. El Niño occurs every three to seven years and its effects are world wide observed. In Australia and Southeast Asia it brings extreme drought, and in the west the deserts of Peru bloom due to abundant rain and east Africa is either hit by extreme drought of flooding. The El Niño event of 1982 and 1983 was the most severe of the 20th century. Other recent occurrences began in 1972, 1976, 1987, 1991, 1994, 1997 and 2006-07. A strong El Niño has not been observed since 1997.

What is causing El Niño?

In short: El Niño is the occasional development of a warm ocean current along the Peru Coast as temporary replacement of the cold Peru Current which normally flows in this region. Under normal circumstances the air pressure over the cold waters off the coast of Peru is quite high. In the west, however, over the warm tropical waters of the western pacific, air pressure is normally low. The difference in air pressure creates an airflow from east to west creating the trade winds which push sun-warmed surface waters westward and exposing cold water to the surface in the east. During El Niño, however, the easterly trade winds collapse or even reverse due to a change in air pressure. The low pressure over the west is trading places with the high pressure normally prevalent in the eastern pacific. As this happens, the wet weather conditions normally present over the western Pacific moves to the east, and the arid conditions of the Peruvian coast appear in the west.

Historians and El Niño

The El Niño phenomenon is known for hundreds years, but exists certainly much longer. It is one of the tasks of environmental historians to find evidence of El Niño-effects in old records. This can probably shed more light on the impact of El Niño on the world’s climate and world history. To guide historians and others interested in the phenomenon, a selected bibliography of El Niño is presented here

Links to El Niño Websites:

Aceituno, P (1988) On the functioning of the Southern Oscillation in the South American Sector. Part I: Surface Climate. Monthly Weather Review, 116, p. 505-524. Part II Upper air Circulation. Journal of Climate, 2, p. 341-355.

Allan, R.j. (1989) ENSO and Climate fluctuations in Australasia. In: T.H. Donnely & R.J. Wasson (Eds.) Climanz III proceedings of the third Symposium of the late quaternary Climatic Histry of Australasia, University of Melbourne, 28-29 November 1987, pp. 49-61.

Allan, R.J. (1993) Historical fluctuations in ENSO and Teleconnection Structure since 1879: Near-Global Patterns. Quaternary Australasia Papers 11/1. Meeting held at Monash University, 2-4 December 1992, pp. 17-27.

Anon. (1991) Report of the workshop on ENSO and climatic change. United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), Environmental & societal impacts group of the National Centre for Atmospheric research. Bangkok, Thailand, 4-7 November 1991, 28 p.

Berlage, H.P. (1966) The Southern Oscillation and world weather. Mededelingen en verhandelingen 88, Koninklijk Nederlands Meteorologisch Instituut, 152 p.

Bliss, E.W. (1925) the Nile flood and world weather, Memoirs of the Royal meteorlological Society, Vol 1, No. 5, pp. 79-85.

Bradley, R.S., Diaz, H.F., Kiladas, G.N. en Eischeid, J.K. (1987), ENSO signal in continental precipitation records. Nature, Vol 327, pp. 497-501.

Changnon, Stanley, A., and Gerald D. Bell, eds. (2000) El Niño, 1997-1998: The Climate Event

of the Century, New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caviedes, César N. (2002) El Niño in History: Storming through the Ages, Gainesville Fla.: Florida University Press.

Davies, M. (2001) Late Victorian Holocausts; El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, New York: Verso Books.

Diaz, H.F. and Markgraf, V. (eds.) (1992) El Niño, historical and paleoclimatic Aspects of the Southern Oscillation. Cambridge University Press.

Diaz, H.F. and Pulwarty, R.S. (1994) An analysis of the time scales of variability in centuries long ENSO-sensitive in the last 1000 years. Climatic change, 26, pp.317-342.

Eltahir, E.A.B. (1996) El Niño and the natural variability in the flow of the Nile River. Water Resources Research, Vol. 32, no.1, pp. 131-137.

Enfield, D.B. (1989) El Niño, past and Present. Review of Geophysics, 27, pp. 159-187.

Fagan, Brian M. (2000) Floods Famines and Emperors: El Niño and the Fate of Civilization, London: Pimlico.

Fraedrich, k and Muller, K. (1992) Climate anomalies in Europe associated with ENSO Extremes.International Journal of Climatology, Vol. 12, pp.25-31.

Glantz, M.H. (1984) Floods, Fires and Famine: is El Niño to blame? Oceanus, 27(2) pp. 14-19.

Glantz, M.H. (1996) Currents of change. El Niño’s impact on climate and society, Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

Grove, R. (1997) The East Indian Company, the Australians and the El Niño; colonial scientists and the emergence of an awareness of global teleconnections. Discussion paper 231, department of Economic History, australian National university, Canberra.

Grove, Richard H. and John Chappell, eds. (2000) El Niño: History and Crisis, Cambridge: White Horse Press.

Grove, Richard, “Revolutionary Weather: The Climatic and Economic Crisis of 1788-1795 and the Discovery of El Niño”, in: Griffiths, Tom, Tom and Libby Robin, Libby, (eds.), A Change in the Weather: Climate and Culture in Australia (Canberra: National Museum of Australia Press, 2005).

Kane, R.P. (1990) ENSO relationship of Rainfall in different regions of India. Revista Braseliera de Meteorologia, Vol. 5(2) pp. 417-430.

Kiladis, G.N. and Diaz, H.F. (1986) An analysis of the 1877-1878 ENSO episode and comparison with 1982-83. Monthly Weather Review, Vol. 114, pp. 1035-1047.

Lindesay, J.A. and Vogel, C.H. (1990) historical evidence for Southern Oscillation – Southern African Rainfall relationships. International Journal of Climatology, Vol. 10, pp. 679-689.

Liu, Y and Ding, Y. (1992) Influence of El Niño on weather and climate in China. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, Vol.6, No. 1, pp. 117-131.

Meggers, B. (1994) Archaeological Evidence for the impact of mega-Niño events in Amazonia during the past two millennia. Climatic change, 28, pp. 321-338.

Nicholls, N. (1988) More on early ENSOs: Evidence from Australian documentary sources. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, Vol. 69. No. 1, pp. 4-6.

Nicholls, N. (1989) How old is ENSO. An editorial Essays.Climatic change, 14, pp. 111-11.

Ortlieb, l. and Machare, J. (1993) Former El Niño events: records from western South America. Global change and Planetary change, 7, pp. 181-202.

Philander, S. George, Our Affair with El Niño: How We Transformed an Enchanting Peruvian Current into a Global Climate Hazard (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004).

Quinn, W.H. and Neal, V.T. (1983) El Niño occurrences over the past four and a half centuries. Journal of Geophysical research, Vol. 92, No. C13. Pp14,449-14,461.

Ramusson, E.M. (1985) El Niño and variations in climate. American Scientist, Vol. 73, pp. 168-177.

Rebert, J.P. and Donguy, J.R. (1988) The Southern Oscillation Index since 1882. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission technical series. Time series of ocean measurements, Vol. 4, Unesco, pp. 49-53.

Richardson, James B. (1998) Early Maritime Economy and El Nino Events at Quebrada Tachhuay. Science281: 1833-1835.

Richardson, James B. (2001) Variation in Holocene El Nino Frequencies: Climate Records and Cultural Consequences in Ancient Peru. Geology 29(7):603-606.

Schove, D.J. and Berlage, H.P. (1965) Pressure Anomalies in the Indian Ocean area, 1796-1960. Pure applied Geophysics, 61, pp. 219-231.

Stahle, D.W. and Cleaveland, M.K. (1992) Reconstruction and analysis of spring rainfall over Southeastern U.S. for the past 1000 years. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, Vol 73, No. 12, pp. 1947-1961.

Stahle, D.W. and Cleaveland, M.K. (1993) southern Oscillation extremes reconstructed from tree rings of the Sierra Madre Occidental and Southern Great Plains. Journal of Climate, Vol.6, No.1, pp. 129-140.

Trenberth, K.E. (1984) On the evolution of the Southern Oscillation. Monthly weather Review, Vol. 115, No. 12, pp. 3078-3096.

Walker, G.T. and Bliss (1934) World weather V. Memoirs of the Royal Meteorological Society, 4, No. 36, pp. 53-84.

Wang, S. (1992) Reconstruction of El Niño event chronology for the last 600 year period. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp.47-57.

Whetton, P. and Rutherford, I. (1994) Historical ENSO Teleconnections in the Eastern Hemisphere.Climate change, 28, pp. 221-253.

Zhang, X., Song, J. and Zhao, Z. (1989) The Southern Oscillation reconstruction and Drought/Flood in China. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 290-301.

Recent Comments